TASMANIAN DAM CASE IS A CONSTITUTIONAL MORAL FAILURE FOR ANIMALS

I'm still wondering why anyone is celebrating environmental cases when nature is probably about as fun to live in as North Korea.

In Australia, environmental constitutional law has previously functioned as the major constitutional source which regulates society’s obligations toward non-human animals.[1] Relevantly, s 51(xxix) of the Australian Constitution bequeaths upon Parliament capacious discretion to legislate with respect to “external affairs” and therefore make laws on many subjects, which includes issues pertaining to the enforcement of Australia’s international obligations, including environmental provisions which affect animals in nature.[2] In this article, I will interrogate two cases nationally celebrated as touchstones of environmental jurisprudence Commonwealth v Tasmania [1983] HCA 21 (‘Tasmanian Dam Case’) and Booth v Bosworth [2001] FCA 1453 (‘Flying fox case’)[3] to demonstrate why both ultimately fail at advancing any meaningful protection for non-human animals, and instead, reinforce only their instrumental value, contingent upon human interests and concerns.

The External Affairs Power: Tensions between Environmental law and Animal Rights Theory (ART)

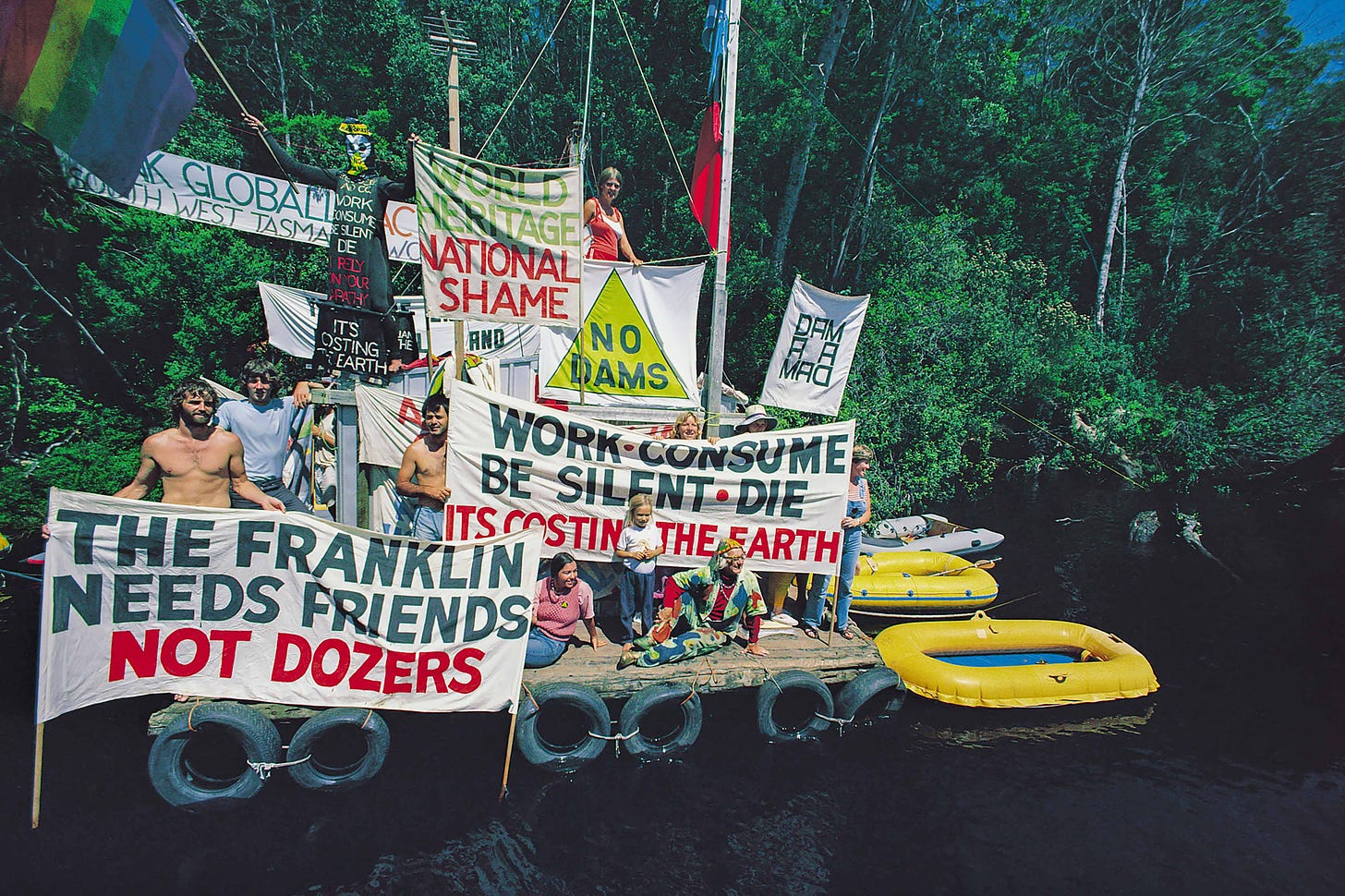

Australia is signatory to a wide range of international treaties, including environmental protection treaties which are enforceable at the domestic level, via the external affairs power, as witnessed in the Tasmanian Dam Case.[4] In this case, the High Court, split 4 -3, prevented the proposed construction of a hydro-electric dam in South-West Tasmania by the Tasmanian Government and several other States, finding in favour of the Commonwealth.[5] The Court held that the Commonwealth had power under s 51(xxix) (‘the external affairs power’) of the Constitution to effectively stop construction over the dam due to international obligations arising under the World Heritage Convention and other environmental treaties to which Australia was a party.[6] The case was essentially, inter alia, a battle between the Commonwealth and the State Government of Tasmania over the extent of the Commonwealth’s ever expansive constitutional powers pursuant to s 51 (xxix). It is now widely accepted the Australian Commonwealth Government has power to enact legislation reasonably appropriate to fulfil international obligations, with Mason J recognising that the external affairs power was intended to be ambiguous and capable of almost unlimited expansion.[7] The Tasmanian Dam Case has been universally celebrated by the contemporary environmentalist movement and is a benchmark case in Australian Constitutional law, widely considered the most famous, influential environmental law case which determined the parameters and scope of constitutional power with respect to environmental conservation.[8]

This case may appear promising as a basis for considering the constitutional protection of non- human animal rights. For example the following idea may be put forward: that because this case has preserved nature, it has therefore also preserved animal homes and lives and it therefore offers a kind of constitutional protection to animals that matters. Further, in so far as wild animals may be considered as belonging to “nature,” they are potentially protected where environments are protected. However, upon closer inspection, the success of the Tasmanian Dam Case from a conservationist perspective is not as easily transferable to animal focused objectives, and in fact, contain implications that are detrimental to the ultimate goals of animal rights and protection.[9] This is because the conception of animals under Australian environmental law is almost always conditional upon whether their existence improves the state of nature and ecology, not because environmental law recognises the intrinsic value of animals or the direct duties which are owed to them upon realisation of such value.[10]

The principles relating to environmental conservation established in the Tasmanian Dam Case mirror broader concepts entrenched in classical environmentalist literature, such as the preservation of nature in spite of animal suffering. For example, Leopold coined the term ‘land ethic’ as the embodiment of environmentalist philosophy, which emphasises a moral duty to the land.[11] Leopold is one scholar whom contributed to a substantial body of work in western philosophy to conceive of wild animals as worthy or attracting moral consideration from humans.[12] However, consideration of animals in environmentalism often only reinforces the subordination of animals to humans and the environment and renders their violent realities in nature either morally acceptable or invisible.[13] For example, wild animals have been conceived mostly through utilitarian terms amongst environmental philosophy and literature, and their value is largely determined by how they contribute to the ecosystems.[14] Removal or slaughter of wild animals is often permitted if it benefits the environment, for example, hunting of deer or rabbits is permitted in designated areas around the world.[15]

Conservationist theory thus embodies the idea that the lives of animals are measurable through their relationship with, and contribution to, the natural world. For example, article 2 of the World Heritage Act, which the Commonwealth relied on to show Australia must honour international obligations in the Tasmanian Dam Case, defines and contextualises animals as part of “natural heritage” and “geological and physiographical formations” which constitute the habitat of threatened species of animals and plants of “outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation,”[16] The “National Conservation Strategy” also adopts the three main objectives of “living resource conservation”, including the protection and improvement of cultivated plants and domesticated animals.[17] There was no mention of animal interests specifically in the case judgement itself, an omission which reflects the greater omission of the interests of animals as moral beings or legal subjects with interests, within at least most environmentalist thought.

The Flying Fox Case is an Australian Federal court case that is also met with similar reverence and embraced as a landmark decision in environmental litigation.[18] In that case, an injunction was successfully sought against the building of electric grids which would have killed tens of thousands of Spectacled Flying foxes.[19] The Flying Fox Case may be ostensively, a case which might seem aligned with ART goals and a positive endorsement of animal protection – after all, the case judgement ultimately ruled in favour of preventing the construction of a grid which would have resulted in the death of thousands of animals,[20] and maintained a precedent which could be relied upon for future, similar protection.

However such an understanding of the Flying Fox Case with respect to animals proves inattentive to a degree, to the true goals of ART. While the Flying Fox Case is not directly related to constitutional interpretation, the case demonstrates, similar to the Tasmanian Dam Case, important trajectories in environmental constitutional law, which function as primordial barricades to obtaining constitutional rights for animals. Here, I identify two main arguments which establish the assertion that the Flying Fox Case (and the Tasmanian Dam Case) undermines core principles of ART and challenge rather than support long term goals of animal advocacy. The first argument I put forward which shows these cases are problematic for ART, is the fact that the courts determine the value of animals according to their function within an ecosystem, including the animals’ ability to promote and contribute to biodiversity, rather than any intrinsic moral value.[21] The second argument I raise is the fact that the courts have reinforced a view of animals which limits their rights as a collective or whole population and not as individuals, both stances of which are largely incompatible with the view that animals ought to be considered individual legal subjects to whom direct duties are owed.[22]

To elaborate, the first argument I put forward above is realised when the Court allocated primary significance to the value of animals upon the “heritage values of the West Tropics World Heritage Area” which contributes to the “character of the Wet Tropics Heritage Area as one of the most significant regional ecosystems in the world” and as an important and significant natural habitat for in-situ conservation.[23] Akin to the Tasmanian Dam Case, the Flying Fox Case also held that an animal’s value is mostly reducible to the value they contribute to nature and the environment, with special emphasis on animals as a species, rather than individual beings.[24] For example, the court emphasized that the lives of the flying foxes were important for the most part because of the value they added to biodiversity.

Branson J said:

“…I am consequently satisfied that the Spectacled Flying Fox contributes to the world heritage values of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area as part of the record of the mixing of the faunas of the two continental plates. I am further satisfied that the Spectacled Flying Fox contributes to the world heritage values of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area on the following bases. First, I am satisfied that the Spectacled Flying Fox contributes to the genetic diversity and biological diversity of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. For this reason I am satisfied that the species contributes to the character of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area as a "superlative natural phenomena" by reason of its being "one of the most significant regional ecosystems in the world". Secondly, for the same reason, I am satisfied that the species constitutes part of the biological diversity for which the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area is a most important and significant natural habitat for in-situ conservation.”[25]

The Flying Fox Case therefore unambiguously assigns to the flying foxes in question a value that is almost completely contingent upon how their existence enriches the broader habitats and eco-systems, not on any, (even remote – animals and morality are not discussed at all) idea of the intrinsic moral nature of animals, or any discussion of potential reform to their legal status.

The second argument stipulated above (that the environmental values espoused in cases such as Flying Fox undermine ART because the rights assigned to animals are collective, rather than individual) is demonstrated when the court concluded that imposing the grid would result in the deaths of nearly half the fox population and should therefore be prevented.

The court said that:

“…the Court accepted expert evidence that the total Australian population of Spectacled Flying Foxes in early November 2000 did not exceed 100,000. On that basis, the Court, again assisted by expert evidence, concluded that the probable impact of the operation of the Grid, if allowed to continue on an annual basis during future lychee seasons, will be to halve the Australian population of Spectacled Flying Foxes in less than five years. Such an impact would be sufficient to render the species endangered within that time frame.”[26]

Here, the obligation to protect animals arises only where there is a threat to a whole population, rather than to an individual which is, as mentioned prior, incompatible with ART, and ultimately the moral-legal direct duties owed to animals should they be recognised as subjects of Australian law. It should be acknowledged that environmental laws and policies such as this do result in the protection of certain animal species, for example in New South Wales all native birds, reptiles and mammals are protected by legislation,[27] however, this protection only exists to a limited degree and is contingent upon an animal being of a certain species, not on the basis of intrinsic value or legal rights. Thus the Tasmanian Dam Case and the Flying Fox Case illustrates that environmental law has capacity to protect the lives of animals, however, this protection is limited and arguably undermines long term goals of recognising animals as legal subjects on the basis that they possess intrinsic moral value.

The tension between ART and conservation is a noted debate in environmental and animal ethics and stems from the difference in perspective regarding the moral value of animals.[28] The underlying objective of environmentalism and conservationism is to preserve biological diversity.[29] When individuals are treated as a collective, it is virtually impossible to further the objective of animal legal status reform or enact meaningful laws and evoke direct duties from the State and its citizens.

Thus, while Australian jurisprudence and cases such as the Tasmanian Dam Case and Flying Fox Case have had a genuinely powerful impact on elevating the status of environmental issues and in some instances, have also protected animals;[30] this protection is fraught because it is conditional upon their contribution or value to nature (therein channeling a more indirect duty approach to animal interests). Hence, the protection to animals under these environmental-constitutional avenues possesses significant limitations. One such limitation is that it has insofar not offered any direct, deliberate, or purposeful means of positive state intervention for animals in times of peril (or really considered taking action on animal suffering in nature in any meaningful way). Henceforth, it is proposed a more tenacious model or provision of animal protection is needed, one that can not only provide the framework for recognising positive intervention to aid animals, but also one that is actually equipped and able with resources and technology that can address and alleviate that suffering experienced by animals. This new framework or model may be a reinterpretation of another constitutional provision, s 51(vi) which is commonly referred to as the defence power and allows for state intervention during times of war, violence or other modes of harm.[31]

[1] Section 51 also empowers the Commonwealth to legislate upon fisheries in Australian waters beyond territorial limits, s 51 (x), the acquisition of property on just terms from any State or person for any purpose in respect of which the Parliament has power to make laws, s 51 (xxxi) and, expansively: “matters incidental to the execution of any power vested by this Constitution in the Parliament or in either House thereof, or in the Government of the Commonwealth, or in the Federal Judicature, or in any department or officer of the Commonwealth.” See Australian Constitution s 51 (xxix).

[2] Murphy J said that in order for a law to have an international character, it is sufficient that it: implements an international law or treaty; deals with things inside Australia of international concern, see The Commonwealth of Australia v State of Tasmania (1983) 46 ALR 625 [729] (‘Tasmanian Dam Case’).

[3] Booth v Bosworth [2001] FCA 1453 (‘Flying Fox Case’).

[4] For example, see Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Convention).

[5] Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 627.

[6] Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 628.

[7] Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 669.

[8] The Tasmanian Dam Case is the most famous and influential environmental law case in Australian history. It was also a landmark in Australian constitutional law, see Environmental Law Australia, Tasmanian Dam Case <http://envlaw.com.au/tasmanian-dam-case/>; see also: Roberts et al, The Tasmanian Dam Case 30 Years On: An enduring legacy (Federation Press, 2017).

[9]Michael Hutchins and Christen Wemmer, ‘Wildlife Conservation and Animal Rights: Are They Compatible?’ (1986) WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 111, 128.

[10] Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 637.

[11] Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (Oxford University Press, 1949).

[12] JB Callicott ‘Animal liberation: A triangular affair’ (1980) (2) Environmental Ethics 311-38.

[13] Leopold above n 270; it should be noted a small handful of constitutional provisions around the globe have begun to recognise the intrinsic value of animals, breaking away from the standard environmental clauses which indirectly capture animal interests, unfortunately Australia is not amongst the handful yet, see Jessica Eisen and Kristen Stilt, ‘Protection and Status of Animals’ (2016) Max Planck Encyclopaedia of Comparative Constitutional Law [MPECCoL].

[14] See generally Norman Myers, ‘Tbe Sinking Ark’ (Permagon Press, 1979); Alastair Gunn, ‘Why should we care about rare species?’ (1980) 2(1) Environmental Ethics 17-37.

[15] William Shaw, Meanings of wildlife for Americans: Contemporary attitudes and social trends, Transactions North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference (1974) 39:151 – 155; Lynne White, ‘The historical roots of our ecologic crisis’ (1967) Science 155: 1203-07.

[16] World Heritage Convention art 2.

[17] Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 732.

[18] Flying Fox Case (n 254).

[19] Flying Fox Case (n 254) at 12.

[20] Flying Fox Case (n 254) [47] – [50].

[21] Flying Fox Case (n 254) at [67] and [68] per Branson J; Tasmanian Dam Case (n 253) 625 at 732.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Flying Fox Case (n 254) [18] and [19].

[24] Flying Fox Case (n 254) at [67] and [68] per Branson J.

[25] Flying Fox Case (n 254) at [67] and [68] per Branson J.

[26] Flying Fox Case (n 254) 3 – 4.

[27] Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (NSW) pt 2.

[28] Hutchins and Wemmer above n 268; further, animal rights pioneers such as Regan and Singer have both strongly criticized a conservative environmental “collective” view of animals (Regan dubbed the view which favoured nature conservation over the well- being of animals as ‘eco fascism’ see Regan, The Case for Animal Rights (n 25) ch 9).

[29] Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (NSW).

[30] Australian Constitution s 51 (xxix); Sylvia Lorek and Dors Fuchs, ‘Strong sustainable governance – precondition for a degrowth’ (2011) Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2011) 1- 8.

[31] Australian Constitution s 51(vi).